Both George Eliot’s Middlemarch and Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady are interested in the connection between visual images and the people who look at them or see them, especially in moments when their characters feel deep grief or despair. These novels both feature scenes where after traumatic experiences in Rome, the female protagonists, after leaving Rome, have a poignant encounter with an image. Julia’s miniature strikes a deeply sympathetic chord in Dorothea for the first time. Comparably, on the night of Ralph’s death, Isabel has an encounter with his ghost. Eliot and James, with these scenes heavily focused on the effect of an image on its viewer, acknowledge the power of the visual in exploring the possibility or impossibility of an alternate self with alternate experiences and transcending even death for Dorothea and Isabel, respectively.

Isabel’s sighting of Ralph’s ghost raises the questions about the inevitability of her suffering and whether she could have occupied the main role of a different plot. Right before stating that “[Isabel] knew a spirit was standing by her bed,” James, suggesting readers to turn back the clock to an earlier moment in the timeline of the plot, explicitly points to the first, joking suggestions about the ghost between Isabel and Ralph, who “told her, the first evening she ever spent at Gardencourt, that if she should live to suffer enough she might some day see the ghost with which the old house was duly provided” (624). By placing the early lighthearted moment in which Isabel expresses to Ralph in language a fanciful but strong desire to see a ghost next to the wordless materialization of Ralph’s ghost at the end of the novel, James perhaps suggests a causal relationship between the utterance of the words and the appearance of the striking image described by the words much later in the novel. Isabel’s partly joking, partly overconfident insistence to Ralph, “‘I’m afraid of suffering. But I’m not afraid of ghosts’” (102) , which Ralph characterizes as “rather presumptuous,” could read a bit like the equivalent of a hubristic challenge to the Fates, a verbal lead on to her own suffering born out of her presumptuousness, as confirmed by the powerful visual sighting of Ralph’s ghost (James 101). With her words alone to Ralph, Isabel perhaps causes the fairytale elements prevalent early on in the novel that bring her boundless wealth and independence, to also perversely grant her wish of seeing a ghost by having her “apparently [fulfill] the necessary condition” of suffering during the course of her novel (James 624). The final materialization of Ralph’s image as a ghost would serve as evidence of that fulfillment. By having Isabel see Ralph’s image as a ghost in confirmation of her suffering throughout the novel and having his readers recall the earlier moment in which Ralph lays down the necessary conditions for seeing a ghost that turns out to be himself, James creates a sense of unavoidable cyclical inevitability. Isabel’s determined desire to distinguish “‘miserable knowledge’” that brings suffering from “‘fond knowledge’” made up “‘of happy knowledge – of pleasant knowledge’” and only pursue the “‘fond knowledge’” has inevitably failed (James 101). Ralph’s ghost-like image intruding upon Isabel’s sight in confirmation of the content of Ralph’s lighthearted banter at an earlier time in the novel’s plot, suggests she could not have arrived at that alternate end devoid of suffering for herself.

At the same time and contradictorily, Ralph’s ghost suggests the opposite, that Isabel’s suffering was not inevitable and that she potentially could have chosen an alternative life path in which she pursues knowledge without suffering. After all, Ralph was not always the haunting image of Gardencourt’s ghost. For most of the novel, and certainly at the point when he first playfully speculates about Gardencourt’s ghost, Ralph is undoubtedly corporeal, alive, and of flesh and blood, even if his illness has done much to waste him away, suggesting that the ghost in the form of Ralph from Isabel’s perspective could not have existed before the moment of his death. Prior to that, the ghost has no confirmable form of definite shape. In other words, the ghost, the embodied confirmation of Isabel’s suffering, at its mention early in the novel and throughout most of the novel, up until the very moment of Ralph’s death, is merely a speculative, symbolic concept, made up by Ralph for witty banter in explanation of their “theories” on knowledge and death (James 101). The theoretical ghost bears no confirmed, embodied weight as definite proof of Isabel’s suffering until the moment of Ralph’s death. The image of the Gardencourt ghost, proof of Isabel’s suffering, is not a permanent or continuously existent image, which makes the path of suffering associated with it similarly indefinite. Though the discussion of Gardencourt’s ghost may have the quality of a Faustian deal, the sense that Isabel should be careful for what she wishes for, the fact that the final image of the ghost only takes on the specified form of Ralph at his moment of death suggests that initial discussion of a generalized Gardencourt ghost, created in a moment of jest and not particularly associated with Ralph’s image, perhaps does not lock Isabel onto a definite, specific path of suffering early on in the novel.

Even if the final image of Ralph left to Isabel as a ghost paired by James’s narration with its initial mention in conversation decisively indicates that Isabel could not have avoided her suffering, the cyclical inevitability associated with the image does not exclude the possibility of alternate paths for getting to the endpoint of having suffered as confirmed by the appearance of the ghost. To reiterate, the ghost could not always have been Ralph owing to the fact that he is clearly alive for much of the novel. In fact, when Ralph first conceptualizes the ghost with Isabel, in addition to being initially dismissive of it, calling Gardencourt “‘dismally prosaic’” with “‘no romance but what you [Isabel] may have brought with you’” (100), when he later begins to play along with Isabel’s fanciful notion of a ghost, he suggests it as another image, another portrait in the Gardencourt separate to himself that, in his words, “‘I might show it to you [Isabel]’” (James 101). From that characterization of the ghost, he represents it as a sight he implies to himself as having seen from “‘[suffering] greatly’” himself, but possessing an identity and existence separate from himself at this point in the novel that he can look upon as a separate entity (James 101). The ghost both is and is not Ralph at different points in The Portrait of a Lady, suggesting that its identity, the final form it takes on in its haunting of Isabel is variable, not set in stone as Ralph. Ralph, in his attempt to set Isabel free by giving her a fortune, ends up bringing her the most suffering, a fact that likely contributes in part to him appearing as the ghost of suffering with “his kind eyes” that has unwittingly brought suffering to Isabel (James 624). But if Ralph had not been the one to decide, without Isabel’s knowledge, on that course of action resulting in Isabel’s suffering, the ghost may have appeared as someone else. Isabel, in that case, may have experienced an alternate life in which the one who brings her the most suffering is not Ralph and so Ralph is not the image of the ghost left with Isabel at the end of the novel.

While Ralph’s ghost presents a haunting visualization of questions related to whether Isabel was fated to suffer and whether she could have had an alternate experience different from the one depicted in The Portrait of a Lady, Eliot does not associate images, such as Julia’s miniature, with an ominous prophetic quality. The mention of the Gardencourt ghost in conversation paired with its embodied appearance in the form of Ralph leads to consideration of whether Isabel’s suffering was predetermined or whether the ghost had to take on Ralph’s form, but Julia’s miniature remains a consistent symbol of, in Casaubon’s words, “‘an unfortunate marriage’” during Dorothea’s initial sighting of it before marriage and later intense focus on it after her return from her honeymoon in Rome (Elliot 76). Unlike in Isabel’s case, there is no suggestion that the earlier dialogue about Julia’s miniature, in which it was first characterized as the representation of “‘an unfortunate marriage,’” should be considered as potentially the moment in which the outcome of Dorothea’s marriage being unhappy was inevitably determined. After all, even Eliot seems to deemphasize questions about a cyclical or confirmatory relationship between Dorothea’s first look and words and comments about Julia’s miniature and her reflections about it after her marriage. Eliot, in that later moment of reflection, refers only to Dorothea’s bygone “memories,” like many of Dorothea’s other “ideas and hopes,” and does not explicitly mention the first conversation about Julia’s miniature between Dorothea and Casaubon (Eliot 275).

There is also nothing “theoretic” about Dorothea’s initial response to Julia’s miniature, no sense that her words will come back to haunt her in confirmation. Dorothea’s words are very much invested in the moment of seeing the portrait, as she makes comments on Julia’s appearance, how it is “‘peculiar rather than pretty’” and lacks “‘even a family likeness between her and [Casaubon’s] mother’” (Eliot 76). Eventually, Dorothea does “[wonder] a little” about the comment Casaubon makes about Julia’s “‘unfortunate marriage’” but her response, rather than containing the presumptuous challenge to destiny Ralph catches in Isabel’s words, is very much concerned with not being “indelicate” by “[asking] for any information which Mr Casaubon did no proffer” (Eliot 76). Early on, Isabel shows a very active interest in pursuing the Gardencourt ghost and concerning herself with the questions about knowledge and inevitable suffering associated with it, while Dorothea only seems to show an interest in passing as a curious outsider. Had Celia never asked Dorothea, “‘will you not have the bow-windowed room upstairs?,’” Dorothea perhaps would not have even noticed Julia’s miniature in the first place (Eliot 75). Unlike Isabel, Dorothea does not actively seek out knowledge about Julia’s portrait to consider questions of suffering in relation to herself, so the consideration of Julia’s portrait later next to its first emergence in the narrative does not raise questions about predetermined suffering materialized from seemingly inconsequential words in the same way Ralph’s ghost does in The Portrait of a Lady. Isabel’s sighting of the ghost during Ralph’s death has a theoretic, speculative, and unsettled quality when considered in relation to the Gardencourt ghost’s initial mention in lighthearted conversation, while Julia’s portrait, though consistently representing “‘an unfortunate marriage,’” only gains personal meaning and receives intense focus from Dorothea after the tribulations of marriage to Casaubon she experiences during her honeymoon in Rome. Julia’s miniature never has a potentially ominous quality of inevitability born from words: it bears no direct relation to Dorothea’s own marital happiness and had Dorothea ended up with a successful marriage, she perhaps would never have given Julia’s portrait a second look herself after her return from her honeymoon in Rome.

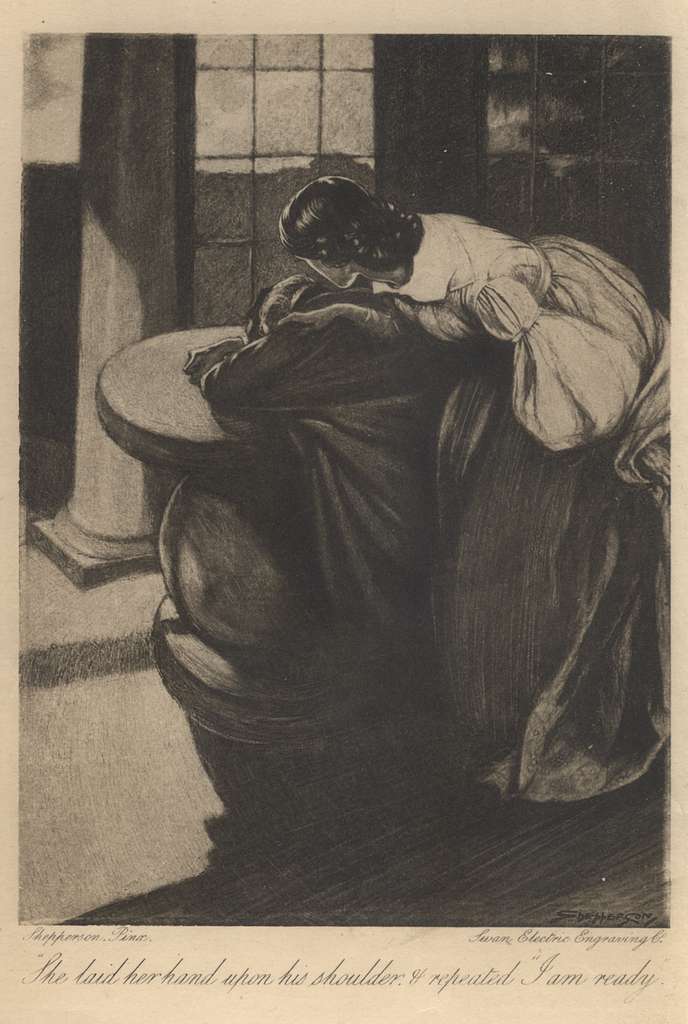

Nonetheless, only during this moment of Dorothea looking at Julia’s miniature hindsight, when “She felt a new companionship with it, as if it had an ear for her,” does the narrative hint at the idea of an alternate self for Dorothea. The deeply sympathetic questions Dorothea asks of Julia’s miniature in free indirect discourse, “Was it only her friends who thought her marriage unfortunate? Or did she herself find it out to be a mistake, and taste the salt bitterness of her tears in the merciful silence of the night?,” in addition to being one way for Dorothea to project onto another object, referred to with the more distancing third person pronouns of “she,” “her,” and “herself,” discomforting questions that she has subconsciously about her own marriage but is not yet ready to directly of herself, they also express a yearning towards undoing a “marriage” deemed “unfortunate” and “a mistake,” full of “the salt bitterness of her tears,” indicative of regret. Essentially, Dorothea considers if she could have done otherwise than end up in an unhappy marriage with Casaubon. She perhaps even wonders what an alternate, unmarried life looks like. In her “bitterness” from having knowledge of what marriage with Casaubon is really like, Dorothea suggests a yearning for an alternate self that did not marry Casaubon.

The questions Dorothea asks of Julia’s miniature that she is actually asking of herself also suggests Dorothea’s sense that she and Julia are perhaps melding into one, a fact Dorothea emphasizes by a sense of her interchangeability with Julia’s portrait. Though Dorothea looks at the miniature, Julia also “beamed on her with that full gaze which tells her on whom it falls that she is too interesting for the slightest movement of her eyelid to pass unnoticed and uninterpreted” (Eliot 275). The boundary between looker and portrait becomes blurry and, by extent, interchangeable. Dorothea and Julia, at this moment, with their shared compassion and interchangeable positions seemingly share the same identity, in which the questions Dorothea asks of Julia also apply at the same time to herself. Julia’s unhappy experiences in marriage also, as a result, seemingly bleed into Dorothea’s ongoing experiences, providing Dorothea with an alternate self and alternate set of experiences from Julia.

But does Dorothea’s intense focus on Julia’s miniature actually provide her with an alternate self? Julia’s experience of an “unfortunate marriage” predates Dorothea’s marriage and, in fact, occurs long before Dorothea is even born, rendering a strictly chronological overlap or meeting completely impossible. Nonetheless Julia’s experiences are perhaps not really so different from Dorothea’s own unhappy marriage that she can legitimately consider it as a separate and distinct alternative to her own. After all, the sense that Julia’s portrait has a life of its own, with “colours deepened,” “lips and chin [that] seemed to get larger,” and “hair and eyes [that] seemed to be seeding out light” is very much the product of Dorothea’s agitated mind bring to life what is simply a representation of a deceased person arrested in time in paint, as emphasized by Dorthea’s first view of the portrait earlier in Middlemarch (Eliot 275). While Dorothea’s experience of Julia’s miniature is moving and seemingly brings her away from her own experience towards that of a long deceased female relative by marriage, it is still, as the narrative seems to suggest, very much an illusion of Dorothea’s own mind inventing a personal relation and with complete knowledge of another human experience, when one does not necessarily exist.

Even Eliot’s narrator seems a bit disturbed by Dorthea projecting an alternate self onto Julia’s miniature. Near the end of this scene featuring Julia’s portrait, when the narrator describes Dorthea “smiling, turning from the miniature” and then “[sitting] down and [looking] up as if she were again talking to a figure in front of her,” the narrator initially creates a sense of ambiguity about whether Dorothea was actually talking to Julia’s miniature by using the simile involving “as” (Eliot 275). Dorothea looks like she is doing so, but is she actually conversing with Julia or is the simile just a mere descriptor meant to give a picture of the attitude in which Dorothea sits? The usually lucid, all-knowing narrator somehow does not have the answer to this question, perhaps in an attempt to shield this disturbing moment of Dorothea’s mental agitation from the reader or to compassionately give Dorothea some privacy in this moment of intense vulnerability. Regardless, Eliot’s narrator, who has generally exhibited the ability to peer deeply in the souls of the novel’s characters, to be able to access characters’ motives long in the past and far into the future, backs away from this moment of ambiguity, suggesting the narrator’s own reluctance about Dorothea seemingly takes on the alternate experiences of Julia, which are really just a projection of her own. In fact, the narrator leaves clarifying the ambiguity to Dorothea herself, with her sudden exclamations, “‘Oh, it was cruel to speak so! How sad—how dreadful!’” breaking through the long, preceding paragraph of narration to clarify that she was, in fact, “[speaking] so” with Julia’s miniature (Eliot 275). To the narrator watching Dorothea objectively outside of herself and the reader only receiving the narrator’s observations in that moment, outside of Dorothea’s imagination, no conversation with Julia has occurred. Julia’s miniature merely remains a silent, unmoving record of an “unfortunate marriage” locked away in the past, long after anything can be done to rectify it (Eliot 275). Essentially, in identifying with Julia’s portrait and seeing in her portrait an illusory alternate experience, Dorothea is really just identifying with a dead artifact that, as powerful as it may appear for a moment in her imagination, records a permanent, unchangeable past.

While Julia’s miniature is essentially a dead end, suggesting a comforting illusion of a potential alternate self without actually providing one, Ralph’s ghost, in the very moment of its sighting, functions differently for Isabel. Unlike in Middlemarch, in which Eliot’s narrator eventually reveals that any communion Dorothea has with Julia is confined just to her mind, James maintains ambiguity about whether Ralph’s ghost, in the moment that it appears to Isabel, is an embodiment only she sees or whether the reader would also be able to see Ralph’s ghost. For example, the sighting occurs after Isabel has “closed her eyes” (James 624). There is an ambiguity to this description that does not clarify whether Isabel only sees Ralph in a hazy dream state or whether Ralph’s materialization as a ghost actually occurs in front of Isabel and outside of herself, making her “[start] up from her pillow as abruptly as if she had received a summons” (James 624). That Isabel knew Ralph closely when he was alive also contributes to the sense that there exists a certain degree of separation between Isabel and Ralph’s ghost. When Ralph was alive for much of the novel, he operated autonomously and independently from Isabel, possessing the capability to even make decisions about her future without her knowledge. In the moment of his death, when Ralph, to Isabel’s perception, becomes a ghost, there is nothing to suggest otherwise than his autonomy and will separate from that of Isabel, in which he may come and go as he pleases.

In addition, James does not back away from the moment of Isabel’s wordless communication with the ghost, in which “She stared a moment; she saw his white face – his kind eyes” and intuitively is “only sure” about Ralph’s passing (James 624). Instead of retreating behind a simile, James directly confronts how “It seemed to [Isabel] for an instant that [Ralph] was standing there – a vague, hovering figure in the vagueness of the room,” rather than leaving it to Isabel herself to reveal her communication with the ghost, which Eliot does in Dorothea’s case (James 624). There is no surprise moment, such as with Dorothea, where Isabel clarifies with dialogue that she has been engaging only within her own mind in conversation with an image of the dead. With the conditional phrase “It seemed to [Isabel]” and the repeated use of the word “vague” or “vagueness,” James emphasizes the hazy, supernatural atmosphere of the scene, while still refusing to clarify if an outside observer, such as the reader, should see the ghost that Isabel sees, despite Isabel clearly seeing it for herself. While ghosts and communication with the dead does not exist in the world of Middlemarch beyond the mind of its female protagonist, the scene with Ralph’s ghost in The Portrait of a Lady does not clearly deny or confirm the existence of ghosts and the possibility of communing with the dead. The visual of Ralph’s ghost and Isabel’s perception of it injects the moment of Ralph’s death with a flavor of the gothic genre, opening up the generally realistic world of The Portrait of a Lady with a sense of vast possibility reaching beyond even life itself towards the supernatural.

Certainly worth noting, is the sense of immediacy invested in Ralph’s ghost, how it changes from moment to moment unlike the static representation of a failed marriage in Julia’s miniature, unchangeable by the hands of the living. The Gardencourt ghost, which takes the form of Ralph at the end of the novel, possesses a shifting identity with unclear purpose towards Isabel. While Julia’s miniature is always a representation of Julia and her marital unhappiness, the ghost is unstable, with an identity and even meaning that shifts over time. To reemphasize, for much of The Portrait of a Lady, the Gardencout ghost remains a theoretical, speculative concept used to explore ideas like suffering and knowledge, only having its identity pinned down at the end of the novel with its embodiment in the form of Ralph. There is also the sense that Ralph only gradually grew into becoming the Gardencourt ghost, a confirmation of Isabel’s suffering after gaining knowledge, during the course of the novel, seeing as to how he himself jokingly treated the Gardencourt as a speculative concept separate from himself in conversation with Isabel at the beginning of the novel. The description of Ralph’s ghost as “vague” and “hovering” also suggests its momentary, shifting nature and how it changes from moment to moment with no stable form associated with a particular identity. Again, the Gardencourt ghost did not necessarily have to take on the form of Ralph. Ralph as a ghost is also, in itself, a transitory state, a moment of change of passing from life to death where it only communes with Isabel for the blink of an eye before disappearing into “nothing” (James 624).

The reason for this visually haunting scene being Ralph’s final appearance to Isabel is similarly unsettled and difficult to pin down. Even after the lengthy deathbed scene in the chapter in which Isabel and Ralph seemingly confess everything to each other, once again, Ralph appears silently and briefly before Isabel for one last time. Why, then, is the final impression that Isabel has of Ralph a haunting ghost that represents her suffering? One potential answer is that this final, intensely visual moment emphasizes that as much as Ralph may like to see himself as and paint himself as a benevolent person in Isabel’s life with a “white face” and “kind eyes” he is still the haunting specter of suffering that has forever changed Isabel’s life for the worse (James 624). After all, Ralph, much like the idea of a haunting, suffering ghost, watches over Isabel but cannot actively do anything to help or protect her from Osmond and even, in fact, unwittingly brings about the conditions that cause Isabel to suffer. Ralph’s ghost, which appears briefly and quickly disappears, is perhaps a final farewell to her, representing how whatever has haunted Isabel and brought her suffering is now disappearing. The “necessary condition” of the fateful words uttered lightly in conversation by Isabel and Ralph has been fulfilled and, now Isabel is free to move on with her life, to not be mired in the specter of her past.

For Dorothea, while Julia’s miniature is an arresting sight, it does not necessarily give her true knowledge beyond herself or truely allow her an approach to a set of alternate experiences. The conversation she has with Julia is very much in her head, so rather than gaining true knowledge from communing with the dead, her reaction to Julia is perhaps more so a projection of her own thoughts in the moment. In contrast, Isabel’s encounter with Ralph’s ghost gives her potentially more knowledge than anyone else. In addition to having potentially more knowledge than those actually present at Ralph’s deathbed during his moment of passing, since Ralph’s ghost suggests that, spiritually, Ralph’s soul and consciousness are actually with her in his last moments, the ghost even gives Isabel an idea of what happens after death, of the potential, embodied existence of the supernatural and the afterlife, which perhaps even contributes to her sense that “life would be her business for a long time to come … she should some day be happy again. It couldn’t be she was to live only to suffer; she was still young, after all, and a great many things might happen to her yet,” including the supernatural experience with Ralph’s ghost (James 607).

The possible transcendence of death in The Portrait of a Lady associated with Ralph’s ghost and the ghost’s shifting unsettled identity, which suggests that visuals and identities can change over time opens up the way for Isabel to change. While Ralph’s ghost initially seems to imply a locked down fate of destined suffering, upon closer inspection, that is not the case. In fact, Ralph’s ghost opens up questions about whether Isabel could have not suffered. Isabel is not locked down in the moment of the powerful but transient visual’s conception. Instead, there exists ground for interpretation and the arrival at even contradictory meanings. Ralph’s ghost is not static like Julia’s miniature, mired in its suffering and marital unhappiness. Rather, it is one of many momentary, alterable images that change from second to second, giving momentary insight into another person before another image may come along to change that view quickly. They are a good way, according to James, for understanding one’s own life and the identities of others constantly in flux and taking on alternate forms. Ultimately, Isabel feels no way to turn away from the visual of Ralph’s ghost, letting it disappear into “nothing” on its own, while Dorothea physically turns away from Julia’s miniature in the end, suggesting her own recognition of it as a dead end, despite the sympathetic connection she has with it (James 624). Dorothea “rose quickly and went out of the room … with the irresistible impulse to go and see her husband and inquire if she could do anything for him,” perhaps out of the recognition that Julia’s miniature mires her in an already determined past and keeps her under the illusion that it is an escape to an alternate life.

Works Cited

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. Penguin Classics, 1994.

James, Henry. The Portrait of a Lady. Penguin Classics, 1986.

Leave a comment