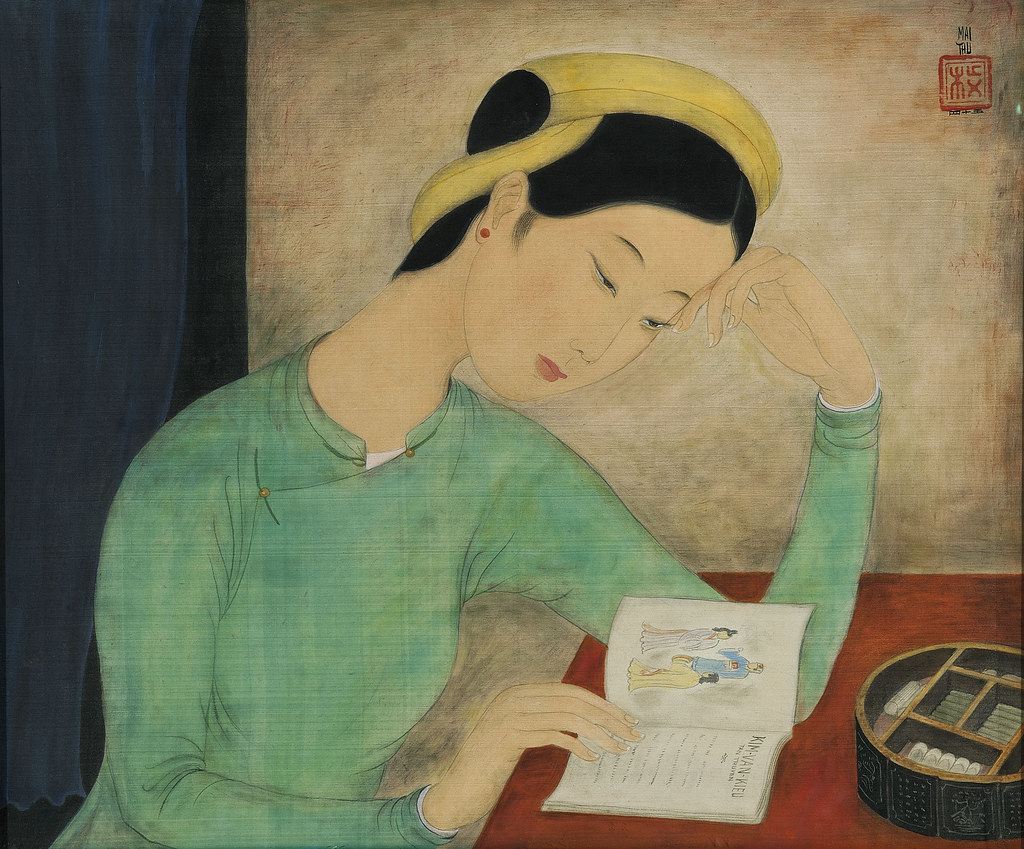

Both Du’s The Tale of Kiêu and Kim’s The Nine Cloud Dream are interested in the role of prostitutes in settings governed by Confucianism. The Nine Cloud Dream includes the major characters Ch’an-yüeh and Ching-hung, courtesans who eventually become Shao-yu’s concubines. The titular main character of The Tale of Kiêu endures working at a brothel. Though all of these women are skilled in the arts and poetry that are highly valued in the Confucian tradition, the evaluation of their expertise in their respective, Confucian worlds is different. While the treatment of courtesans in The Nine Cloud Dream seemingly extends a form of idealized Confucian meritocracy to women, The Tale of Kiêu, though it also creates spaces for women to practice systems of Confucian values, frequently depicts the powerful twisting arguments of meritocracy and pairs these abuses with the exploitation of Kiêu’s talents. Upon closer examination of courtesan culture, The Nine Cloud Dream also ends up revealing the limitations of women navigating Confucian systems meritocracy, but the conclusions of both novels suggest an underlying reliance on the reader’s role of imagining alternative systems for the women.

The Nine Cloud Dream suggests an overlap between the party overseen by the courtesan Ch’an-yüeh and the civil service exam based on Confucian values that Shao-yu later takes. While the setting of the party, with its “dozen young men … with a score of pretty girls sitting on silk cushions, laughing and chatting among tables laden with fine food and wine” seems more casual and lighthearted than the presumably more systematic and regulated procedure of administering a civil service exam, the mechanism for evaluating the worthiness of those who partake in each social function is the same (Kim 32). To evaluate the merit of the men, in both the setting of the civil exam and the party, they must engage in “composing poetry,” a skill that is meant to prove the artist’s mastery of the Confucian texts and, by extension, Confucian virtues (Kim 32). As though hinting at the somewhat surprising overlap between a civil service exam and the party of poetry-composers that Ch’an-yüeh oversees, the narrative has Shao-yu introduce himself as “‘a humble scholar from the country on my way to take the civil examination’”(Kim 32). The mention of “‘[scholarship]’” and “‘examination’” early on in the scene only further suggests how the environment of the civil examination, with its use of knowledge on poetry and literature as measure of Confucian virtue, has permeated and integrated itself into a setting of seemingly greater revelry and lightheartedness.

But at the party, in the position of the exam administrator, typically a minister who has proven his Confucian virtue by years of successful governance and, before that, first passing a civil exam to become a minister, is not another formally educated man. Rather Ch’an-yüeh, a courtesan, is in that position that comes with it the power of discernment. The partygoers are clear about Ch’an-yüeh’s Confucian merits: “She is an unrivaled beauty, classically trained, and also an excellent critic. That is why everyone in Lo-yang submits his poems for her expert opinion. She never errs in her judgment” (Kim 33). Because she possesses so many merits as a courtesan, she, in accordance with her vast talents, is allowed the highest position – one of “excellent critic,” “expert opinion,” and “judgment” – in the world of parties and poetry composition, a more casual extension of the Confucian civil examination system. When the other men attempt to persuade Ch’an-yüeh to break her agreement with Shao-yu to spend her night him, though he has proven his merit by writing the best poem, Ch’an-yüeh, revealing her own virtue over the poetry-writers that she oversees, declares, “‘I have no affection for men who break a promise’” and successfully excuses herself (Kim 35). Though “The men were unhappy about her departure,” they “dared not say a word,” recognizing “their agreement with her,” and by extension her superior judgment earned through the demonstration of her artistic skill. Recognizing Ch’an-yüeh at the top of another Confucian system of meritocracy extended into the world of courtesans, the men have no choice but to defer to her judgements.

Ch’an-yüeh’s investment in the form of Confucian meritocracy afforded to her in the social and public role of overlooking poetry functions as part of being a courtesan is evident for the words she quotes from her friend Ching-hung to Shao-yu: “‘But a courtesan can have her pick, since she can sit with men of renown and open her gates to receive nobles and princes. She learns to recognize the quality of Ch’u-an bamboo, or jade from Lan-t’ien. She has no trouble choosing the best’” (Kim 38). Ch’an-yüeh highlights the rewarding of talented people, “‘men of renown,’” with equally meritorious people, women who can “‘recognize quality’.” Also notable is the esteem she affords to the agency women have in courtesan’s meritocratic system of seeking out the best corresponding and companionate mind to match her own – “‘She has no trouble choosing the best.’” Gone, however, is this sense of agency and equal reward when Kiêu is forced to work as a prostitute for Dame Tú after she has seemingly surrendering up her body, her ability to choose, and even a part of her interiority by crying out, “‘What care I for myself? My fate is set’” (Du.III.1145). Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, the brothel system, with its emphasis on becoming “a mistress of our craft” (1216) through quickly becoming learned in “[learning] seven ploys to catch and hold a man, / eight ways to please in bed (1209-1210), while successfully “[playing] love with them until you’ve played them out, / till heads must swim, till hearts of stone must spin,” is another meritocratic system, as outlined by Dame Tú’s emphasis on the mastery of certain teachings and skills (Du.III.1211-1212).

But this argument of meritocracy is a false and twisted version of Confucian meritocracy, used to exploit Kiêu’s talents, beauty, and ability to learn quickly for the brothel’s profit. In choosing to commodify themselves and their merits, unlike in the world of The Tale of Kiêu, Ch’an-yüeh and Ching-hung receive the desired reward of an equally talented man, Shao-yu, in an extension of Confucian meritocracy to their skillful work as courtesans. Kiêu’s work as a prostitute under Madam Tu bears little resemblance to the situations of Ch’an-yüeh and Ching-hung – Kiêu does her work nonconsensually, emphasized by her prior abdication of “care” for “[herself]” (1145) and how she, though possessing the merit of “learning all” (1217), “[ironically]” (1220) becomes “deadly pale” (1218) from “shame” (Du.III.1219). Dame Tú does not even attempt to hide the transactional baseline philosophy from which she plans to proceed with objectifying Kiêu’s merit and learning: “‘Men are all alike: / they’ll get their money’s worth or won’t come here’” (Du.III.1205-1206). While Dame Tú receives coin from the men who frequent the brothel gain sexual gratification, Kiêu, instead of being truly rewarded with a like-minded gentleman and scholar for the display of her merits, such as in the world of The Nine Cloud Dream, is left violated and feeling ashamed.

Much like how Ch’an-yüeh and Ching-hung are matched in merit with Shao-yu through the practice of their profession as courtesans, Kiêu seemingly eventually meets her match when Thúc, who is of a “well-read breed” comes to visit her at the brothel (Du.IV.1276). Of course, Kiêu’s relationship with Thúc, which “had begun as lust” but “soon turned to love” (1290), does not completely make up for the injustices and lack of agency she has suffered at the brothel from Dame Tú’s marketing and exploitation of her talents and “fame as queen of beauty” (Du.IV.1279). Nonetheless, that Kiêu’s talents attract for her a seemingly like-minded suitor is vaguely reminiscent of Ch’an-yüeh’s exercise of her artistic skills as a courtesan attracting the like-minded Shao-yu, who passes her test of merit based on poetry composition. With Thúc’s emergence, The Tale of Kiêu may, despite its tragic tone, seems initially to somewhat fulfill the idealized Confucian meritocracy promised to courtesans in The Nine Cloud Dream.

Nevertheless, what the narrative presents as somewhat like a reward for Kiêu’s merit ends up being false and bittersweet. Because of Thúc’s failure to inform Hoạn, his first wife, of his marriage to Kiêu, Hoạn and her mother, Thúc’s mother-in-law, plot to torture Kiêu. They kidnap her and bring her to a courtroom, a “stately hall” headed by Hoạn’s mother that is reminiscent of the Confcian court system of ministers and yamens (Du.IV.1721). Much like how Ch’an-yüeh overseeing her poetry composition party is an extension of Confucian meritocracy and civil examinations into the realm of courtesans, Hoạn’s mother oversees an extension of the Confucian legal system into her realm, the private, domestic household. This analogy between a Confucian court and Hoạn’s mother’s court the text explicitly suggests with how the courtroom is “inscribed above” with “‘Heaven’s Prime Minister,’” which hints at the public systems judgment based on Confucian values from which Hoạn’s mother draws inspiration (Du.IV.1722).

But unlike Ch’an-yüeh, Hoạn’s mother is no fair judge of merits, despite analogously occupying a top ministerial position of a Confucian system of rewards and punishments extended to the feminine sphere. During the legal proceedings, Hoạn’s mother “ queried Kiêu, she probed her, root and branch— / Kiêu dutifully answered, told her life,” but rather than recognizing Kiêu’s personhood from her invasive “[probing]” inquiry into Kiêu’s past, Hoạn’s mother essentially abuses her power, refusing to recognize Kiêu’s humanity and merits (Du.IV.1725-1726). Instead, she dehumanizes Kiêu, despite her knowledge of Kiêu’s past, declaring, “‘you’re one of those vagabonds past all shame! / This wench is no good, decent woman, no! / She must have fled her man, if not her lord / A graveyard cat! A hen that prowls the fields’” (Du.IV.1728-1731). Further objectifying Kiêu while completely flattening and discounting her inner life, Hoạn’s mother asserts, “‘I’ve bought you soul and body—you’re my slave, / and yet such airs and graces you display!’” (Du.IV.1734-1735). Unlike the idealized Confucian meritocracy extended to courtesans like Ch’an-yüeh and Ching-hung, Kiêu’s world is pessimistic about the extension of systems based on Confucian values, such as meritocracy, to women, as evident from the unvirtuous, exploitative behavior of women with a degree of power, like Hoạn’s mother and Dame Tú.

Nonetheless, while the gaping holes of Confucian values and systems of meritocracy, especially in relation to women, are strikingly and tragically obvious in relation to Kiêu’s experiences, small fissures emerge in the idealized Confucian world of The Nine Cloud Dream. Ch’an-yüeh’s agency as a courtesan, upon closer examination, turns out to be conditional, still dependent on the respect and “agreement” of the men who place her in an exalted position (Kim 35). From the perspective of the men she entertains, only because “‘We [the men] are all great poets here, and so we cannot be our own judges’” and because “‘We [the men] ask her to choose the best and sing for us, set to music, and then comment on the good and bad points’” does she have her position at the top of a partly version of the Confucian civil examination system (Kim 33). Learning more about Ch’an-yüeh’s reason for becoming a courtesan from her own perspective reveals a tragic past not completely unlike the one in which Kiêu sells herself to save her father and her family from legal problems: “‘We were poor and had no money for [my father’s funeral], so to bury him properly my mother sold me to be a courtesan for one hundred pieces of gold. I swallowed my pride and accepted the shame and sorrow of a life of servitude’” (Kim 36). Ch’an-yüeh language of “‘[accepting] … shame’” and “‘sorrow’” in a “‘life of servitude’” mirrors the language Kiêu frequently uses to lament her own misfortunes, suggesting that had Kiêu been born into The Nine Cloud Dream, she could have easily led Ch’an-yüeh’s life in which she is heavily rewarded for her merits despite an initial loss of agency, and that, conversely, had Ch’an-yüeh been born into The Tale of Kiêu, she could have easily led Kiêu’s almost completely tragic life.

As such, neither text offers any clear solutions regarding the tenuous relation women, especially those working as courtesans or prostitutes, have with Confucian meritocracy. Even the Confucian idealism of The Nine Cloud Dream turns out to have its limits and is ultimately a dream from which Hsing-chen awakens at the end of the novel, preferring his original life as a Buddhist monk (Kim 212-213). Similarly, Kiêu also undergoes a fantastic reawakening or reincarnation at the end of the novel when the Buddest nun Giác Duyên saves her after she drowns herself (Du.VI.2703-2710) – the narrative even characterizes Kiêu’s return to her family as “Kiêu’s resurrection” (Du.VI.3032). Seemingly, both novels seem to suggest a Buddhist alternative to worldly woes related to Confucianism suffered by the characters, including Ch’an-yüeh, Ching-hung, and Kiêu. But, again, Buddhism is an incomplete solution – for example, though Kiêu frequently finds solace in Buddhism, it does not stop her from suffering due to the exploitation of Confucian meritocracy. Rather, the Buddhist themes of waking up from a dream, reincarnation, and resurrection places the impetus on readers to engage in fantastical reimaginings of their own. The reader takes on the responsibility of waking up from injustices hidden even in the most ideal Confucian worlds and thinking up an alternate reality in which the talents and merits of women like Ch’an-yüeh, Ching-hung, and Kiêu are rewarded without accompanying objectification or exploitation.

Works Cited

Du, Nguyên. The Tale of Kiêu: A Bilingual Edition. Translated by Huỳnh Sanh Thông, Yale University, 1983.

Kim, Man-jung. The Nine Cloud Dream. Translated by Heinz Insu Fenkl, Penguin Books, 2019.

Leave a comment